In retrospect, Sept. 11, 2001 would have been a good day to be late, or call in sick. But Sun employee Michael Harding had only been working for the company less than a year, and his office had just moved to Sun’s office in the 26th floor at Two World Trade Center. After a brief chat with co-workers about the previous evening’s Denver Broncos-New York Giants game, he was eager to get to work.

Around a quarter to nine, “I felt something like an earthquake,” Harding said, a feeling he was familiar with as a California native. What he didn’t know is that this was the start of the most harrowing day of his life, leaving more than 3,000 people dead, and reducing an icon of the New York skyline to a smoldering heap of ruin.

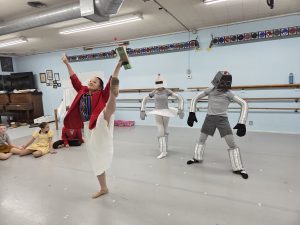

Harding told his story at last week’s Santa Clara Rotary meeting, fittingly on Sept. 11.

His office faced away from One WTC. “We had no idea what was going on. I went to the window and all I could see was smoke and paper,” he said. “What strikes me 13 years later is how much paper there was in the air and on the ground.”

Workers were told to evacuate the building, but there had been fire drills before and it wasn’t uncommon for people to ignore them. “I finally got up and walked to the side of the building and could see crowds of people in the street looking up.” Something serious really was happening. Harding decided to leave.

“I started down the stairs and saw a river of people, and it wasn’t moving fast,” he said. As he made his way down, there was an announcement that a plane hit One WTC, but everyone in Two WTC could go back to work. However, the elevator configuration in the building meant that to get back to the 26th floor, he had to first go down to the lobby.

When he got there, he was headed for the elevator, when a police officer stopped him, saying, “You need to ignore what you heard. We’re going to evacuate the building.” That advice likely saved Harding’s life. He was out on the sidewalk when the second plane “hit the building above my head.”

Immediately he thought, “it’s going to come down on me.” Putting his laptop bag over his head, he ran across the street and crawled under a truck. “And then I saw the big gaping hole in the building I was just in.” He still didn’t know he was at ground zero of a terrorist attack.

As the debris shower abated, Harding wanted to let his family know he was safe. But cell phone networks crashed under the call load, and pay phone lines were 10 deep. Harding kept focused on one thing: getting away from the burning buildings.

So he started walking east, arriving at a friend’s Liberty St. office, where he figured he might find a working telephone. The receptionist stared as he walked into the 56th floor office. “You were there,” she said in a stunned voice. Harding then saw himself in a mirror: covered with dust, clothing torn. The people in that office had seen the whole catastrophe and were in a state of shock.

But Harding wasn’t. His mind was empty of any thought except leaving lower Manhattan. As the group discussed a plan, before his eyes, “The top of the building [Two WTC] starts to disappear. The dust started coming up, and it was coming towards us,” he said.

The roiling dust storm formed an impenetrable curtain. Then they heard a plane overhead and the second building rumbling down. Again Harding focused on one thing: getting away from lower Manhattan.

A stash of out-of-date promotional tee shirts supplied improvised facemasks, and the group ventured out into the street. “It was a blizzard of dust and extremely small particles. You couldn’t see anything,” said Harding.

About 1.5 million people commute to Manhattan, and Harding’s group was among them – all trying to get home. With subway and commuter rail stations under the WTC destroyed, and streets blocked with debris and emergency vehicles, nothing was operating in lower Manhattan. And although one of Harding’s group members had a car, it was locked in an abandoned parking garage.

“The only one way we could get off Manhattan was to walk to Grand Central station, four miles away,” he continued. So they joined the sea of people slowly making their way uptown; people who just hours before may have been investment bankers and janitors, but now were equals in disaster.

Reaching Grand Central hours later, “It was surreal,” recalled Harding. “It looked like Armageddon.” Trains were jam-packed, “like something you’d see in Calcutta – people hanging out windows. The train moved at a snail’s pace. People were quiet and many were staring at me, with shards of glass in my hair, my clothes all torn, covered in dust.”

More than two hours later, Harding finally arrived home, and heard from his daughter the best words he’s ever heard in his life: Daddy’s home! “I didn’t even know what I had been through until I saw it on CNN. All day, all I was focused on was the next step.”

0 comments