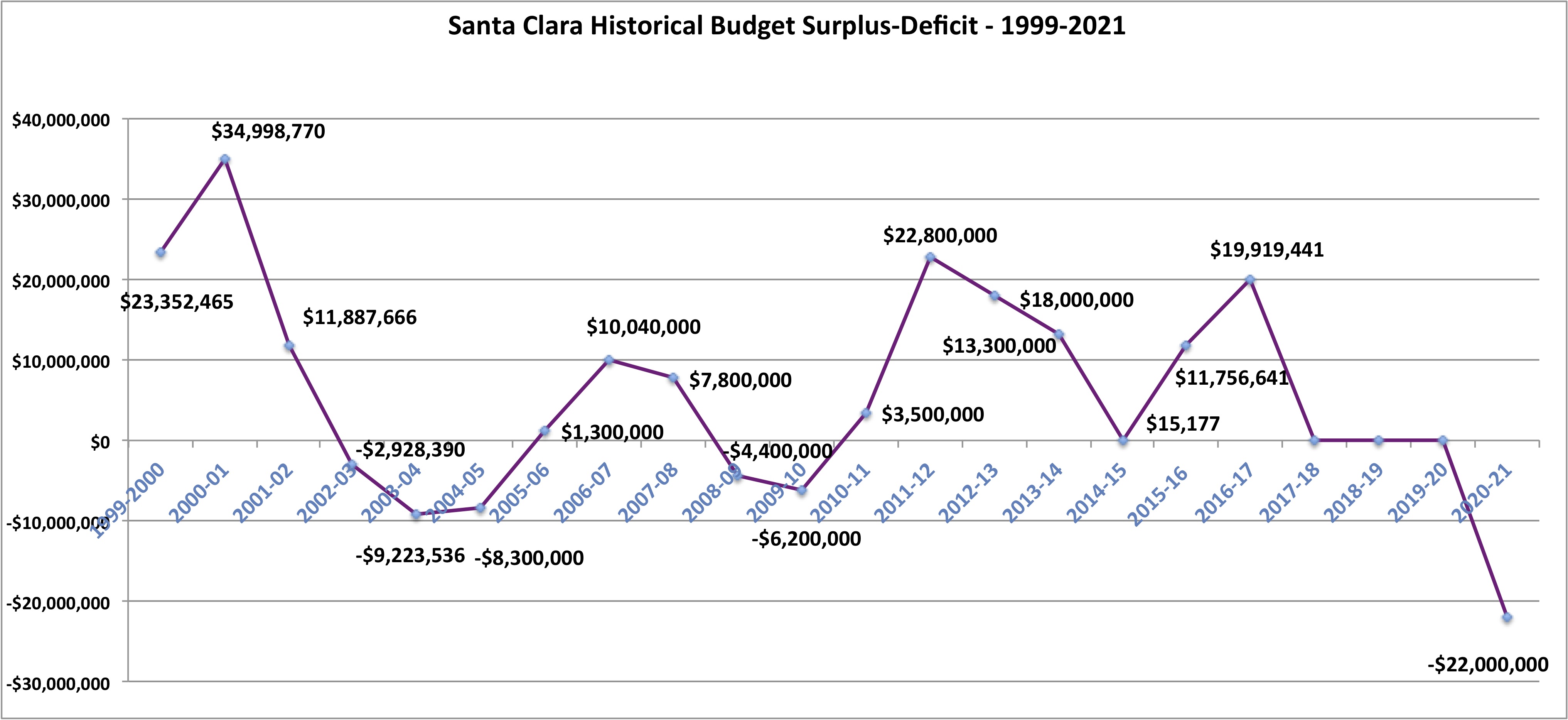

Although their cause is unprecedented, Santa Clara’s current budget woes aren’t an anomaly. Since 2000, the City’s budget has had a structural — chronic — deficit that keeps the City’s budget seesawing between deficits and surpluses. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the pace.

In 2001, the economic crash caused by the dot-com bust and September 11 hit the City budget.

But four years after that crisis, in 2005, then-City Manager Jennifer Sparacino warned that the biggest problem in Santa Clara’s budget wasn’t the economy. It was a structural deficit, Sparacino told the Council, that wasn’t going to be fixed without structural changes that would increase revenue or cut expenses.

History has proved Sparacino’s analysis correct.

From a $34 million surplus in 2000, the City posted a $3 million deficit in 2003. Three years later the City posted a $13 million surplus. Another three years later the City posted a combined $10.6 million deficit in 2009 and 2010, the immediate cause being the Great Recession and the real estate meltdown.

The City Council’s response to these cyclic deficits was not to heed Sparacino’s warnings. It was to spend down the City’s emergency reserves — recently renamed the budget stabilization reserves.

When, in 2011, the reserve accounts held little more than moths — by law, cities must have balanced budgets — the Council finally agreed to act.

“I’ve worked for the City for the last 30 years and the situation is by far the worst I’ve ever seen,” Sparacino told the Council at an April 2010 meeting.

The City froze or left vacant 100 open full-time positions, cut about 10 full-time positions, and negotiated with eight of the City’s employee unions for pay concessions — one day a month furloughs and a moratorium on raises. Two of the City’s unions chose layoffs rather than concessions.

At that time, then-City Manager and elected officials took voluntary salary and stipend cuts. City Hall, library and the Senior Center hours were cut. As-needed staffing and overtime budgets were cut. Funding for outside groups and City events was cut. Fees and charges for services increased. Materials, services, and supplies budgets were pared to a bare minimum.

And the City sold property it owned on Altamont Pass to Silicon Valley Power — a transaction that put cash into the general fund and put the asset on SVP’s books.

The City broke even in 2012 and managed to end the year with a $3.5 million surplus. But most of these measures were one-time fixes.

Furloughs, for example, only affect current payroll. They don’t affect the City’s pension costs, which continued their steep upward climb.

After the crisis passed, hiring and raises proceeded apace, often with higher percentages to compensate for lost pay. And between 2017 and 2020 many new management positions were created and salaries ballooned.

A few things — such as Triton Museum funding, which accounts for about 1/1,000th of general fund spending— were never restored.

As the economy bounced back, the City enjoyed surpluses and rebuilt its reserves after 2012. The opening of Levi’s Stadium delivered about $3 million a year directly to the general fund, as well as increases in sales tax revenue.

Skyrocketing real estate values made property tax Santa Clara’s top revenue source for the first time. New development fees, proposed by former City Manager Julio Fuentes, brought funding for new and renovated parks.

Despite the revenue growth after 2012, surpluses dwindled to nothing in the last two years, with the 2020 forecast showing deficits returning in 2023.

And now, what was expected to be a tiny $100,000 surplus this year has become a $23 million shortfall.

City Hall has taken some action already, as current City Manager Deanna Santana reported in May. These include a hiring freeze, stricter expenditure controls, a 50 percent cut in temporary staff, limits on travel and training, reduced IT and vehicle purchases and a review of current contracts.

Nonetheless, the City will have to spend down $11 million of the budget stabilization reserve to balance the 2020-21 budget. This still leaves over $60 million in the reserve fund.

“We are working with our bargaining units to determine whether they will participate in cost reductions,” Santana wrote in an email. “We will provide updates to the City Council on budget reduction actions in September and other proposals may be necessary for the December 2020 timeframe.”

The City is also looking at long-term revenue boosts, which won’t help the immediate situation, but would help stabilize the budget in the long term. One of these is increasing the hotel tax (transient occupancy tax), which is on November’s ballot. This could generate up to another $7 million for the general fund in future years.

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated for clarity and accuracy.

Music lovers, if you’re free on Thursday, May 1, you might want to take in…

Another ethnic minority group is accusing the Santa Clara Unified School District (SCUSD) of creating…

The Bay Area Air District (BAAD) has fined subsidiaries of Kinder Morgan, Inc. $226,990 for…

After her book discussion group on March 25, Santa Clara resident Carol Buchser stopped off…

Bay Area artist Nathan Oliveira (1928-2010) described himself as an abstract artist whose work had…

The California Highway Patrol's so-called "surge" operations in Oakland have netted nearly 400 arrests so…

View Comments

History should repeat itself. The City Manager down to staff that earns $80,000 per year should voluntarily take a pay cut tapering from 20% to 5%. The City Manager's compensation has always been too high.

Puedo ir hoy