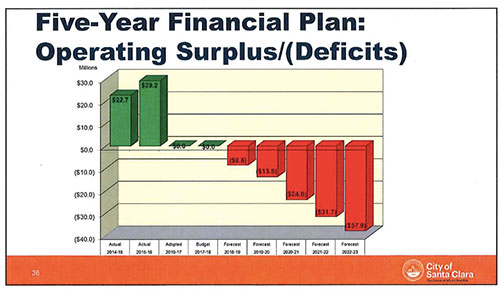

While Santa Clara’s general fund revenues are projected to grow 15 percent from $221 million to $255 million over the next five years, general fund costs are projected to grow at over twice that rate—35 percent—from $219 million to $295 million.

That adds up to a $38 million deficit in 2022-23 and a $116 million collective shortfall over the next five years. Pension costs drive that increase, nearly doubling from $41 million in the coming year to $73 million in five years. (California courts have ruled that pensions cannot be cut, even when a municipality goes bankrupt)

As a percentage of the budget, the 2022-23 deficit would be Santa Clara’s highest in at least two decades. At 13 percent of the 2022-23 budget, it would also set a record, beating 2003-04’s $9 million deficit, which was 8 percent of that year’s $122 million budget.

To change course, Santa Clara’s revenues would have to grow more than twice the forecast. The alternative would be limiting the growth of all non-pension expenditures to a total of 3 percent over 5 years.*

General fund revenues have grown an average of 21 percent over any given five-year period since 2000. Despite the real estate and stock market crashes in 2008, Santa Clara’s revenues grew 17 percent between 2004-05 and 2009-10. From 2010-11 to 2016-17—the period that saw the opening of Levi’s Stadium and an overall economic boom—revenues grew 56 percent.

But what goes up also comes down. From 1999-2000 to 2004-05 revenue dropped 2 percent. Between 2000-01 and 2005-06 it declined 8 percent. And in the four-year period from 2000-01 and 2004-05 Santa Clara’s general fund revenue fell 20 percent.

Although the forecast isn’t betting on dramatic economic growth, it doesn’t factor in any slowdown, according to the May 23 budget report. But there are signs that the Silicon Valley economy is, in fact, slowing.

Rents are dropping, according to apartment search firm RentCafe (rentcafe.com/blog). In the last few months layoffs have been announced at Yahoo!, Hitachi, Paypal and Cisco. Chinese consumer electronics giant LeEco has ditched the ambitious campus that was going to bring 12,000 jobs to Santa Clara. Additionally, the state budget (www.ebudget.ca.gov) forecast is down.

If Santa Clara isn’t depending on the regional economy to lift its boat, how will the City find the additional money to balance the budget?

One alternative is aggressively pursuing new tax revenue sources—in other words, fast-tracking development and re-development, the approach of former City Manager Julio Fuentes. But even the most aggressive development strategy takes years to deliver returns, and any development that would cover the 2018-19 shortfall needed to be under construction now.

One of the projects that could have helped cover that shortfall was Irvine Corp.’s Mission Town Center mixed-use development, originally proposed two years ago in 2015.

The project—on six acres of Old Quad land that’s currently housing an aging warehouse and yielding a few thousand dollars in tax revenue—would have delivered at least $1.25 million in one-time development fees and nearly $400,000 in new tax revenues, according to a March 2015 presentation to the City Council. The Council reduced the size of the project twice. In 2016 Irvine withdrew its proposal saying the Council’s constraints combined with the price of the land lease made the development economically unfeasible.

Another resource for covering the deficit could be sales of Santa Clara land formerly owned by the defunct RDA—estimated in 2012 to be worth $300 million. The first of those sales, the land under the Hilton, has been negotiated for $24 million. The City receives about 10 percent of property tax revenues, so about $2.5 million of the sale proceeds will come to Santa Clara. But even if all the land were sold for, say, $500 million, Santa Clara would only receive $50 million in one-time revenue.

Other routes to new revenue could include increasing fees and service charges, cutting City services, or looting Santa Clara’s reserves, land holdings, and Levi’s Stadium. The legal structure of Silicon Valley Power (SVP) limits the ability of the City Council to touch SVP reserves or cash. All offer short-term fixes but do so at the cost of long-term investment and budget stability.

Poorly maintained roads cost more in the long term than roads that are regularly maintained.

Rapidly increasing fees drive equally rapid increases in resident and business dissatisfaction, and could have a counter-productive effect by reducing enrollment in City programs and less business investment.

Some might look for a budget rescue coming from the stalled Related Companies’ City Place development. Estimates from 2014 show the multi-billion project boosting annual property, sales and hotel tax, land rent and fee revenues by more than $20 million.

City Place’s planned 2016 groundbreaking is now more than a year overdue and indefinitely stalled. The immediate cause is a San José environmental lawsuit. But even if groundbreaking takes place this year and there are no delays in construction, Phase I wouldn’t open until 2020, and full build-out isn’t anticipated until the late 2030s.

Santa Clara got through the deficits of the 2000s by first spending down its reserves and, when that was exhausted, reducing service hours, pay freezes and employee work furloughs. Current reserves of $55 million would plug Santa Clara’s budget gap for less than three years.

*Non-pension expenditures in 2016-17 were $178 million ($219M minus $41M). Those could grow to no more that $184 million ($254M minus $73M) in 2022-23 in order to balance the budget without new revenue.