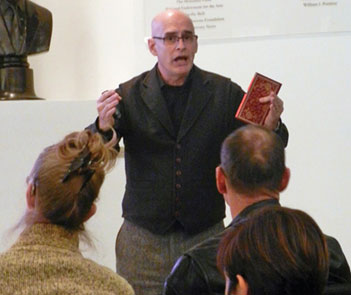

For the final lecture in the Triton Museum of Art’s “A Curator’s Eye: Discerning a Masterpiece” series on March 14, Chief Curator Preston Metcalf had nothing to say. He had spent five weeks laying out the long checklist of criteria that makes a work of art a masterpiece. So instead of defining, Metcalf showed works of art that met every single piece of criteria and explained how those pieces exceeded standard.

To recap, a masterpiece must have ambivalence and irony, strangeness and originality, aesthetic splendor, need to creatively misread its precursors, have cognitive power, be a metaphor, demand re-experiencing, inspire self-change through character inwardness, be larger than any social programming and have achieved anxiety or a fear of mortality.

“I thought about which I should choose and there were some very easy choices that I could have made … I decided to choose one that shows up in all the history books and it’s usually not thought of as a top tier, but it’s certainly a masterpiece,” said Metcalf, who chose Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Judith Slaying Holofernes.”

It has strangeness and originality. “There were plenty of versions of Judith and Holofernes … and [this one] does have a strangeness,” said Metcalf. “The blood squirting out of it. The violence of it. That sets it apart [from other paintings].”

It is ambivalent and ironic. “The violence of it all; it’s ambivalent,” said Metcalf. “We’re rooting for her and yet she’s committing a horrific act … Art as in literature is beyond the dualities of good and evil. Therein lays the ambivalence. The irony? The irony is the subject that portrays the subject – namely the model, Artemisia Gentileschi herself. That’s Artemisia’s self-portrait as an allegory of painting. The irony is … she puts her own self-portrait in the painting. So now not only is she the creator, she’s the instrument of destruction.”

There is aesthetic splendor. “It’s certainly splendorous,” said Metcalf. “It’s executed well. It speaks to the sublime.”

“Judith Slaying Holofernes” also creatively misreads its precursor, Gentileschi’s role model, Caravaggio’s work, and it’s done in his signature, theatrical, baroque style.

Gentileschi’s piece has cognitive power. “I think the fact that we can see her coming to terms with the traumatic event of her life [she was raped] tells you that she is aware of the cognitive power,” said Metcalf. “Cognitive power means that the creator is aware and they are portraying that awareness in their work. This is one of the most difficult things to see in a masterpiece at times because in order for you to recognize that the creator is aware, you have to be aware.”

It’s a metaphor for Gentileschi’s personal trauma, and in a larger sense, a metaphor for anyone who has been damaged.

The painting demands to be re-experienced. “If any of you just learned something that you did not know about that painting before, but you’ve seen the painting before, then … you’ve re-experienced it … The next time you see it, you will look at it differently.”

There is self-change through subject inwardness, but Gentileschi’s entire body of work needs to be viewed. “Twelve years after the first work was done … she moved more and more into scenes of Judith slaying Holoferenes after the fact … I like to think that somehow she was able to rise above the pain and this is her statement: ‘you will not defeat me,'” said Metcalf.

It is larger than the counter-reformation social programming that was happening at the time, and became the issue of her personal trauma – trauma that could be anybody’s personal trauma.

Finally, the death scene has achieved anxieties and a fear of mortality. “So there you go,” said Metcalf. “That’s one of Western art’s great masterpieces. It shows up in all the art history books.”

Metcalf will begin a new lecture series, “Seven Works of Art that Changed the World,” on Thursday, April 24. Visit www.tritonmuseum.org for more information.

0 comments