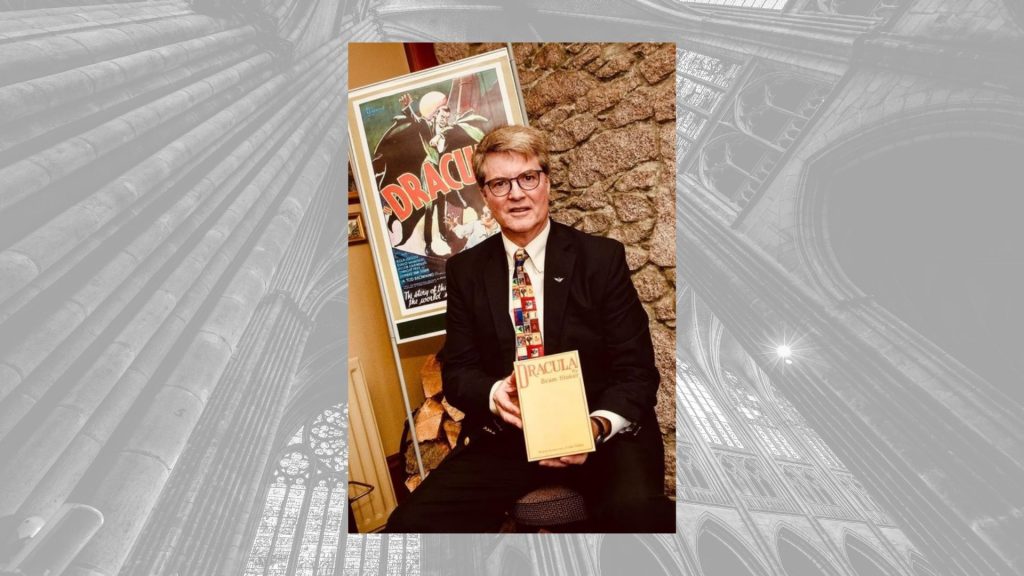

Meeting Dacre (pronounced like ‘acre’) Stoker for the first time, you wouldn’t be surprised to know that this amiable man with his ruddy good looks was an Olympic athlete, is a lover of the outdoors, and, with his wife, director of a nonprofit dedicated to preservation and protection of Aiken, SC’s grand trees.

He couldn’t be further from the image of his great-granduncle Bram Stoker’s immortal vampire Dracula.

Yet Stoker is also one of the world’s foremost authorities on his famous ancestor and the Dracula myth. He’s the manager and curator of the family’s literary estate and co-author of two vampire novels, Dracul and Dracula — The Undead, prequel and sequel, respectively, to his great-granduncle’s book — and The Lost Journal of Bram Stoker, the Dublin Years.

Stoker visited the South Bay in December at the Menagerie Market Yuletide Fair at the Winchester Mystery House and gave a series of talks on his great grand-uncle, the vampire myth, and Dracula in literature and movies. Stoker leads tours of Bram Stoker’s Britain, Ireland and Romania’s Transylvania region. He’s also has appeared in TV documentaries about the endlessly fascinating Dracula story.

Born in Montreal, Canada and retired from two decades of teaching, Stoker describes his life these days as 80% Dracula and 20% trees and himself as a “literary forensic detective.”

“The book has an enduring fascination,” he said. “It’s a book that keeps on giving. It’s not a straightforward story. That’s what keeps people coming back again and again to it.”

He wasn’t “at all a Dracula-ologist” earlier in his life, Stoker says. His research into the Stoker family literary estate began in 2003 when he became the custodian of Bram’s estate — now an international enterprise. Because Bram had few descendants, the material was largely intact when it came down to Stoker.

The archive held a wealth of material about Bram’s research and how Bram constructed his famous book. Stoker used much of the material to develop his own books.

“It was a target-rich environment for us,” said Stoker. “I’m still finding new things. Bram’s notes show that every detail in Dracula is historically accurate. He referenced real people, real places, real events, real train schedules,” he said. “That’s what made Dracula so effective.

“He brings [late 19th century] scientific knowledge and investigation methods together with the supernatural so that all these details are very realistic,” he continued. For example, “Bram’s oldest brother was a doctor and instructed Bram on how to do a transfusion.”

This found its way into Dracula. When Dr. Von Helsing tried to save the life of Dracula’s victim, Lucy Westenra, with blood transfusions.

“It’s a perfect example of modern science vs. Dracula,” said Stoker. “These believable details ease us down a path to where we become open to accepting the unbelievable.”

At the center of Stoker’s research is the source of Bram’s ideas.

“I’m always looking for clues to what inspired Bram, what formed his ideas,” Stoker said.

“The mystery of Bram Stoker begins in his childhood when Bram was confined to bed as a young child with a mysterious illness, for which bloodletting was prescribed,” said Stoker. “Bram’s uncle wrote a treatise on bloodletting. In Bram’s notes, there’s an image of a leech and a note, ‘Idea: leeches attract and repulse,’ and a story his mother told him about people buried alive and crawling.”

One of the buried treasures in the Stoker papers is material Bram’s editor cut from the book, including Bram’s original ending.

“Bram originally had a volcanic eruption bury Dracula’s castle,” said Stoker. “It would have had a definite conclusion.”

Instead, Dracula ends with a bowie knife — instead of a stake — driven through the count’s heart, and none of the customary accouterments of vampire killing: decapitation and a mouthful of garlic.

So Stoker poses the question: Was Dracula really killed? Or is the vampire biding his time, waiting to re-compose himself and once again disturb our sense of reality?

As Stoker’s great grand-uncle put it: “There are mysteries which men can only guess at, which age by age they may solve only in part.”