With the upcoming celebration of Valentine’s Day, sweethearts took part in the tradition of exchanging tokens and trinkets with their beloved. While curmudgeons claim these sometimes costly knickknacks are a conspiracy by card and flower companies to stay in business, the symbols of love are rooted in history, and in the Feb. 6 Coffee with the Curator at the Triton Museum of Art, Chief Curator Preston Metcalf explained the history of the symbolism associated with the day of love.

Originally called Lupercalia–a Feb. 14 holiday when the masters would symbolically trade places with their slaves–the celebration evolved into an “anything goes” day where young men would write their desires on a billet of paper or cloth and give them to young women, often resulting in orgies and pregnancy.

Later, Saint Valentine was jailed for preaching about Christianity. While in jail, he fell in love with the jailer’s daughter and sent a card professing his attraction, which she received as he was being beheaded on Feb. 14.

After Pope Gelasius proclaimed Saint Valentine the patron saint of romance in 496, Romans–even Christians in Rome–were still celebrating Lupercalia and, in an attempt to clean up the celebration, the church Christianized it, eliminating the anything goes mentality. Men, however, continued to give their love interest cards, a tradition continued today.

February flowers, specifically roses, originated with rose windows–spiral, stained glass windows with images of Mary and baby Jesus in the center. “It’s because of the rose window, because of Mary that roses became identified with February,” said Metcalf. “It goes back to this. Before the rose, it was the star. The star was a symbol of the ancient goddess going all the way back to one of the most ancient goddesses of civilizations.”

The leap from cards and flowers to the feelings of love associated with Valentine’s Day came with the Troubadours, and the art of the time.

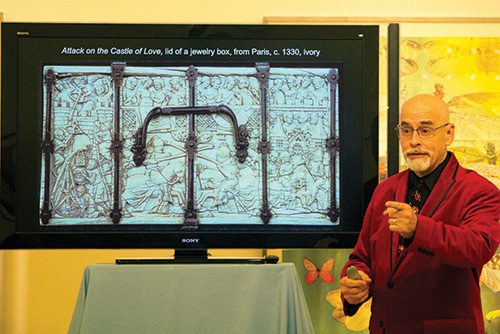

The lid of a circa 1330 jewelry box, Attack on the Castle of Love–two knights jousting below swooning women and Cupid in the top corner shooting his heart-pointed arrow down below–best explains Troubadour amour. “In this age of love,” said Metcalf, “in the age of the Troubadours and romantic love, it would be coming for the knight to go up to a young woman and pledge his servitude to her and if he was very lucky she would give him either a rose or she would tie her scarf onto her lance and he would be her champion … It’s all about romantic love. The church did not like this. They did not like this entire tradition.”

It wasn’t until Jeffrey Chaucer when the modern day idea of Valentine’s Day came to be. “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day when every bride cometh there to choose his mate,” said Metcalf, quoting Chaucer. “That’s how we got it folks. When you get your loved one flowers, chocolates, whatever it may be, you are celebrating a tradition that grew up in the 12th to 14th centuries because you cannot kill the old traditions.”

Metcalf begins an art history lecture series, America: A History in Art, on Thursday, March 2. Visit www.tritonmuseum.org for more information.